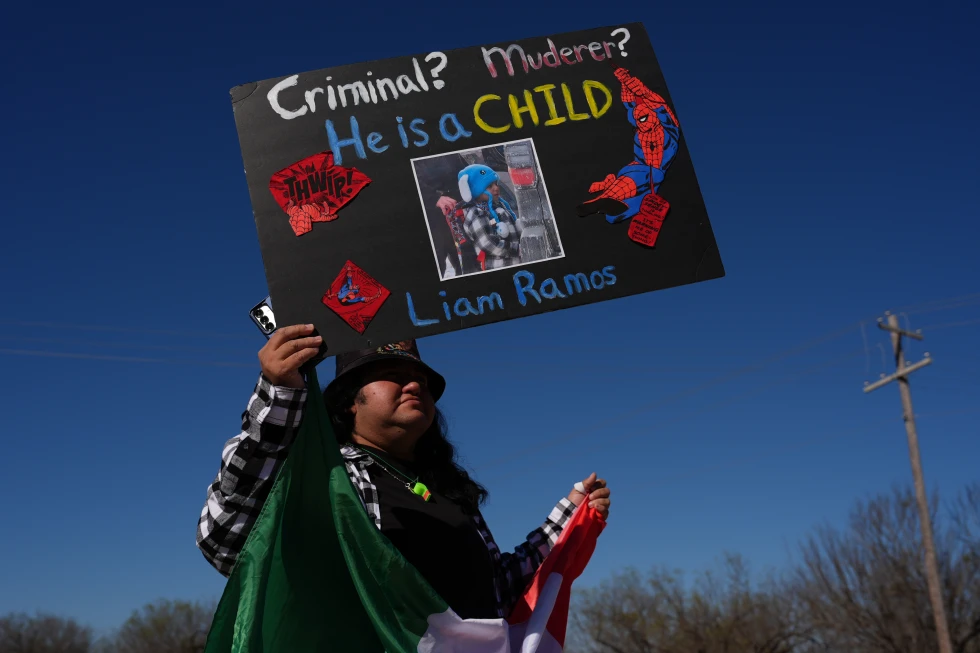

In a significant shift in its juvenile justice policy, Queensland has enacted laws that will hold children as young as 10 accountable under the same sentencing guidelines as adults for severe crimes, including murder and assault. The government justified these measures by citing public demand for increased safety following a perceived rise in youth crime.

Premier David Crisafulli emphasized that the reforms are intended to prioritize the "rights of victims" while asserting they will serve as a deterrent against youth criminals. However, this perspective faces substantial opposition from experts and human rights advocates, who argue that evidence shows tougher sentencing does not effectively reduce youth crime and may, in fact, worsen the situation.

Critics have pointed to statistics from the Australian Bureau of Statistics indicating a significant decrease in youth crime over the past decade, with crimes at historically low levels. This raises questions about the necessity of the new laws, especially when studies suggest that engagement with the justice system can lead to more severe criminal behavior later in life.

The new law, characterized by the slogan "adult crime, adult time," introduces harsher penalties for 13 distinct offenses, with mandatory life sentences for murder cases involving minors. Prior to this, the maximum penalty for juvenile murder convictions was ten years, with life sentences reserved for particularly severe cases. Further amendments eliminate provisions favoring non-custodial options, meaning young offenders could face incarceration more frequently.

Reaction to the legislation has been mixed. The Queensland Police Union praised the reforms as a “leap forward,” while the new Attorney-General acknowledged the conflict with international standards and the expected disproportionate effect on Indigenous youth, who are already overrepresented in detention.

Queensland's commissioner for children condemned the changes as an "international embarrassment," stating that they ignore the adverse effects of exposing vulnerable children to the justice system. Legal experts warned that the new laws could result in more trials as children become less willing to plead guilty under the pressure of harsher penalties.

Despite assurances from the Queensland government of future investments in detention facilities, critics are left questioning the balance between public safety and the rights of young offenders, as the fate of many susceptible youths hangs in the balance under the new legal framework.

Premier David Crisafulli emphasized that the reforms are intended to prioritize the "rights of victims" while asserting they will serve as a deterrent against youth criminals. However, this perspective faces substantial opposition from experts and human rights advocates, who argue that evidence shows tougher sentencing does not effectively reduce youth crime and may, in fact, worsen the situation.

Critics have pointed to statistics from the Australian Bureau of Statistics indicating a significant decrease in youth crime over the past decade, with crimes at historically low levels. This raises questions about the necessity of the new laws, especially when studies suggest that engagement with the justice system can lead to more severe criminal behavior later in life.

The new law, characterized by the slogan "adult crime, adult time," introduces harsher penalties for 13 distinct offenses, with mandatory life sentences for murder cases involving minors. Prior to this, the maximum penalty for juvenile murder convictions was ten years, with life sentences reserved for particularly severe cases. Further amendments eliminate provisions favoring non-custodial options, meaning young offenders could face incarceration more frequently.

Reaction to the legislation has been mixed. The Queensland Police Union praised the reforms as a “leap forward,” while the new Attorney-General acknowledged the conflict with international standards and the expected disproportionate effect on Indigenous youth, who are already overrepresented in detention.

Queensland's commissioner for children condemned the changes as an "international embarrassment," stating that they ignore the adverse effects of exposing vulnerable children to the justice system. Legal experts warned that the new laws could result in more trials as children become less willing to plead guilty under the pressure of harsher penalties.

Despite assurances from the Queensland government of future investments in detention facilities, critics are left questioning the balance between public safety and the rights of young offenders, as the fate of many susceptible youths hangs in the balance under the new legal framework.