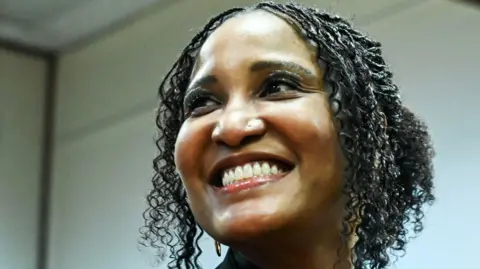

In the bustling capital of Lilongwe, Malawi, Suzanna Kathumba finds herself at a crossroads of despair and determination as she navigates the dire economic landscape. With a monthly salary of 80,000 kwacha (about $46 or £34), the divorced mother of four is increasingly forced to consider how to stretch her meager earnings to provide for her family.

As she wipes down her living room furniture with a cloth, she expresses a poignant sentiment: “I’ve told my youngest children not to get too dirty when playing so we can save on soap.” At 43, her desire to keep her children clean is overshadowed by the harsh reality of rising commodity prices. The pressure is mounting, especially considering that most of her income is directed toward school fees and other essential expenses.

Malawi is experiencing significant economic stress, primarily due to hyperinflation, which recently hit an annual rate of 27.7%. Despite some relief from April’s 29.2%, the inflation remains one of the highest in Africa. Ms. Kathumba laments, "The money finishes before it even comes. We're living a very hard life," encapsulating the struggles faced by numerous citizens in similar circumstances.

The Ernst & Young consultancy has categorized Malawi alongside a few global economies as having a "hyperinflationary economy." Recent reports indicate that Malawi has a staggering cumulative inflation rate of 116% over three years, with projections of continued high inflation into the coming years. The World Bank also classifies Malawi among the world's poorest nations, asserting that approximately 70% of the population lives on less than $2.15 a day.

Desperate times have led Ms. Kathumba, like many others, to forgo savings entirely. "I would be lying if I say that I save some money at the end of the month," she admits. School fees alone consume a significant portion of her income, and the rising prices for essentials like food and soap severely limit her family's quality of life.

Economists attribute Malawi's pressing inflation issues to a persistent shortage of foreign exchange (forex). The nation consistently imports more than it exports, relying on staple crops like maize and soya while needing to buy expensive products such as fertilizers and medicines from abroad. As Dr. Bertha Bangara Chikadza, a senior lecturer in macroeconomics, states, “We export perishable goods but import high-value items, making forex vital.”

The forex shortage has further created a scenario where businesses must resort to the black market for currency, fueling even higher prices for consumers. Mohammed Hanif Waka, a stationery shop owner, speaks of drastically reduced sales and being forced to lay off employees as a direct outcome of inflated costs.

Amid this chaos, protesters have taken to the streets to voice their frustrations over rising prices and the crippled economy. A recent suspension of a $175 million loan agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has further complicated the situation, with calls for fiscal discipline struggling against the backdrop of heightened spending pressures.

While Finance Minister Simplex Chithyola Banda notes the government's priorities in fuel procurement over building reserves, the context is bleak for citizens. As Malawi approaches national elections, addressing inflation and the cost of living has become a pivotal campaign issue.

Trade Minister Vitumbiko Mumba has acknowledged the need for regulation in pricing and forex distribution, reflecting concerns that traders may be exploiting the situation. Yet, as Ms. Kathumba poignantly states, "I hope the politicians remember the less privileged Malawians when making their decisions." In this time of uncertainty, Malawians look for hope, yearning for government intervention and long-term solutions to their economic struggles.