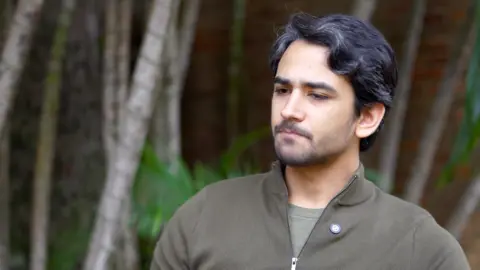

Daniel Chapo, elected president of Mozambique with 65% of the votes in a contentious election, is set to take office on Wednesday, marked by protests and calls for a national strike by opposition groups. Critics, including the leading opposition party leaders, have labeled the election results as fraudulent, igniting protests that range from peaceful demonstrations to violent clashes, resulting in tragic outcomes including deaths and vandalism.

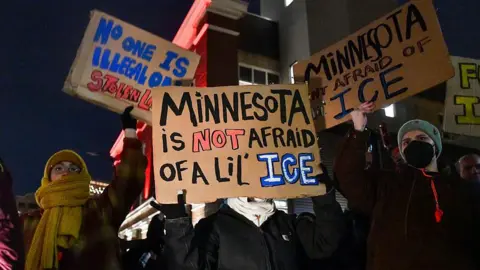

Chapo's main opponent, Venâncio Mondlane, who recently returned from exile after surviving what he claims was an assassination attempt, has urged the public to protest on inauguration day, framing the event as a battle against corrupt leadership. Both Renamo and MDM, the country's significant opposition parties, have announced their boycott of the inauguration, expressing their refusal to acknowledge Chapo's administration.

Despite this hostile environment, some civil society members express a conflicted view of Chapo. Mirna Chitsungo, an activist who has worked with him, admires his commitment to dialogue and respect for civil society, yet acknowledges that he assumes power under dubious circumstances. Chapo's path to successful governance is fraught with challenges, requiring him to mend relations with the populace, tackle corruption, and stimulate economic recovery while being perceived as an illegitimate leader.

With Mozambique facing rampant cartel activities and political factions resistant to change, analysts underline that Chapo's greatest task will be to navigate public dissatisfaction while restoring order in a nation rife with systemic corruption and governance issues. While some hold hope that Chapo may provide a fresher approach compared to the outgoing President Felipe Nyusi's contentious rule, others remain skeptical.

Born in 1977, amidst the civil war that shaped Mozambique, Chapo's rise through the ranks—from media to legal and political realms—has framed him as a man of the people. Yet he is the first president who wasn't part of the independence struggle, which presents a unique duality: he possesses the potential for reform, but many citizens question whether he genuinely represents their voices.

To abdicate the looming crisis, Chapo must forge alliances and actively seek solutions to the political instability, including reforming the electoral process, enhancing national reconciliation, and significantly addressing unemployment. Experts suggest that engaging with Mondlane and other critics may offer necessary support for implementing his agenda.

Critical voices advocate for structural changes within the political fabric of Mozambique as a collective challenge, emphasizing the need to infringe upon the entrenched interests of elite groups while restoring public trust in the governance system. Chapo's upcoming presidency now hinges on his ability to assert authority, address grievances, and unite a divided populace in hopes of mitigating the chaos stemming from the recent elections.