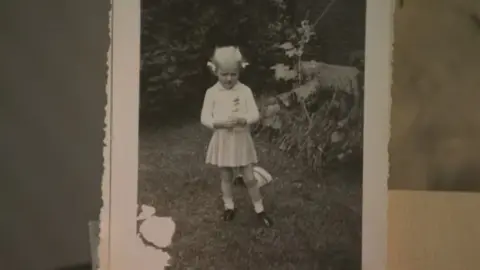

The first thing Lana Ponting remembers about the Allan Memorial Institute, a former psychiatric hospital in Montreal, Canada, is the smell - almost medicinal.

I didn't like the look of the place. It didn't look like a hospital to me, she told the BBC from her home in Manitoba.

That hospital – once the home of a Scottish shipping magnate – would be her home for a month in April 1958, after a judge ordered the then-16-year-old to undergo treatment for disobedient behaviour.

It was there that Ms Ponting became one of thousands of people experimented on as part of the CIA's top-secret research into mind control. Now, she is one of two named plaintiffs in a class-action lawsuit for Canadian victims of the experiments. On Thursday, a judge denied the Royal Victoria Hospital's appeal, paving the way for the lawsuit to proceed.

According to her medical files, which she obtained only recently, Ms Ponting had been running away from home and hanging out with friends her parents disapproved of after a difficult move with her family from Ottawa to Montreal.

I was an ordinary teenager, she recalled. But the judge sent her to the Allan.

Once there, she became an unwitting participant in covert CIA experiments known as MK-Ultra. The Cold War project tested the effects of psychedelic drugs like LSD, electroshock treatments and brainwashing techniques on human beings without their consent.

Over 100 institutions – hospitals, prisons and schools – in the US and Canada were involved.

At the Allan, McGill University researcher Dr Ewen Cameron drugged patients and made them listen to recordings, sometimes thousands of times, in a process he called exploring.

Dr Cameron would make Ms Ponting listen to the same tape recording hundreds of times.

It ran over and over again, you're a good girl, you're a bad girl, Ms Ponting recalled.

The technique was a form of psychic driving, says doctoral student Jordan Torbay, who has researched his experiments and their ethical implications.

Medical records show Ms Ponting was given LSD, as well as drugs like sodium amytal, a barbiturate, desoxyn, a stimulant, as well as nitrous gas, a sedative known as laughing gas.

The harsh truth about the MK-Ultra experiments first came to light in the 1970s. Since then, several victims have tried to sue the US and Canada. Lawsuits in the US have largely been unsuccessful, but in 1988, a Canadian judge ordered the US government to pay nine victims $67,000 each. In 1992 the Canadian government paid C$100,000 (about $80,000 at the time) to each of 77 victims – but did not admit liability.

Ms Ponting was not among them, because she did not yet know that she was a victim, she says.

For decades, Ms Ponting said she felt something was wrong with her, but she did not learn of the details of her own involvement in the experiments until somewhat recently.

She says she had little memory of what happened at the Allan, or in the years that followed. However, she eventually married and moved to Manitoba, where she had two children and became a grandmother. Despite this, she has suffered life-long repercussions from her time at the Allan.

Ms Ponting's experiences still haunt her, leading to recurrent nightmares and reliance on medication to manage mental health issues attributed to her past.

The Royal Victoria Hospital and McGill University declined to comment as the case is before the courts. Nevertheless, for Ms Ponting, the lawsuit represents a chance to finally achieve justice and closure for her traumatic past.

}