Over the years, Kim Visintine kept vigil by her son's hospital bed, trying to understand the rare brain tumor that took his life at just six years old. With every turn of a page in the hospital library, she uncovered not only medical information but also a broader theme echoing in her community of St. Louis, Missouri. Kim's son, Zack, was diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme, an extremely rare childhood cancer that left doctors baffled. Over time, the devastation of this loss led Kim to believe that Zack was not an exceptional case but part of a larger tragedy surrounding Coldwater Creek, an area previously affected by significant nuclear waste from World War II’s Manhattan Project.

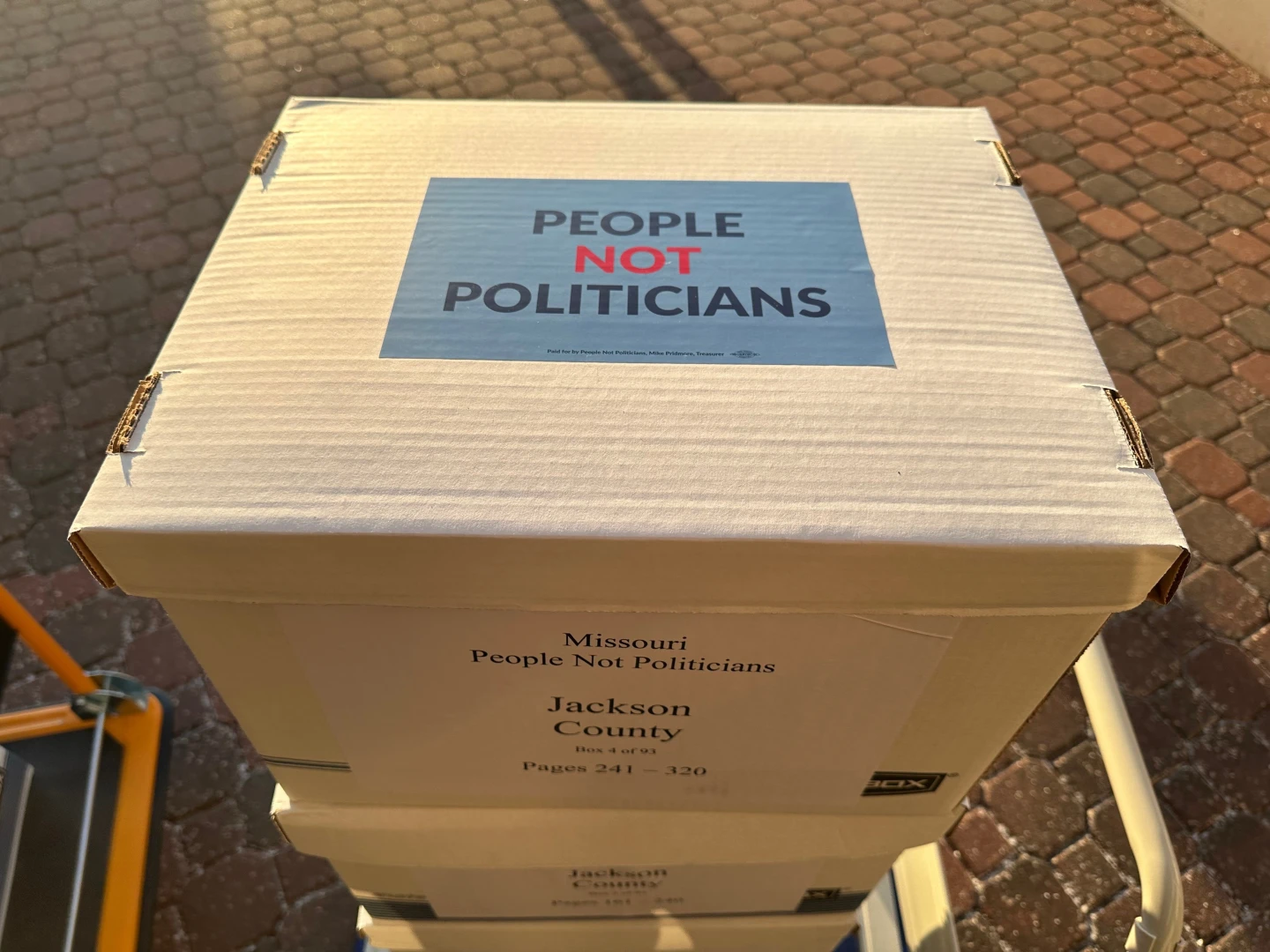

The revelations began as whispers on social media, now escalating into grave concerns that many locals share. Residents in St. Louis claim that powerful officials have turned a deaf ear to the struggles of those exposed to radiation when the atomic bomb was developed. A compensation initiative designed to assist those afflicted by diseases from radiation exposure—the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA)—expired without catering to the needs of the community. This initiative had previously allocated billions to thousands of claimants in areas like New Mexico, where atomic experiments were undertaken.

Despite the need for answers, research remains sparse. Although the National Cancer Institute has linked radiation exposure to specific cancers in the area, the federal report indicated that these increases would be marginal and difficult to trace back to the source of exposure. Cleanup efforts for Coldwater Creek continue, projected to conclude by 2038, but the anxiety looms over those who grew up nearby—like Karen Nickel, who reflected on her seemingly fairytale childhood marred by the deaths of numerous friends from rare cancers.

Residents like Karen share harrowing statistics; she recalls 15 deaths from bizarre cancers among her childhood neighbors. These startling figures raise broader questions about the safety of the environment. The harsh reality hit when Karen's granddaughter was born with an ovarian mass, adding to the horror stories circulating in the community. Together with others, Karen helped establish Just Moms STL, a group advocating for the clean-up and ensuring that locals receive protection from potential future radiation exposure.

Similar stories echo throughout the neighborhood, creating a web of health crises rooted in local histories. Teresa Rumfelt, who lived close to Karen, consistently bore witness to neighbors suffering from rare illnesses, making her worry escalate when her sister was diagnosed with ALS, tying back to the environmental concerns many residents believe are linked to radiation.

Although some professionals might downplay the connection between illnesses and the exposure from Coldwater Creek, the sense of dread persists. Dr. Gautum Agarwal acknowledges attending patients from the area presenting with cancer but points out that statistical evidence remains inconclusive, ultimately suggesting enhanced screening for those living nearby. Roger Lewis, an expert in environmental health, emphasizes that while the perceived risk exists, studies show minimal correlation. Nonetheless, the government’s response to community fears lacks transparency, only heightening worries.

As Kim Visintine aptly conveys, many residents live under the grim inevitability that illnesses will touch their lives sooner or later. This ongoing struggle for the people of Coldwater Creek continues to draw attention as they seek answers and advocacy amidst a troubling history of nuclear waste and health risks.

The revelations began as whispers on social media, now escalating into grave concerns that many locals share. Residents in St. Louis claim that powerful officials have turned a deaf ear to the struggles of those exposed to radiation when the atomic bomb was developed. A compensation initiative designed to assist those afflicted by diseases from radiation exposure—the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA)—expired without catering to the needs of the community. This initiative had previously allocated billions to thousands of claimants in areas like New Mexico, where atomic experiments were undertaken.

Despite the need for answers, research remains sparse. Although the National Cancer Institute has linked radiation exposure to specific cancers in the area, the federal report indicated that these increases would be marginal and difficult to trace back to the source of exposure. Cleanup efforts for Coldwater Creek continue, projected to conclude by 2038, but the anxiety looms over those who grew up nearby—like Karen Nickel, who reflected on her seemingly fairytale childhood marred by the deaths of numerous friends from rare cancers.

Residents like Karen share harrowing statistics; she recalls 15 deaths from bizarre cancers among her childhood neighbors. These startling figures raise broader questions about the safety of the environment. The harsh reality hit when Karen's granddaughter was born with an ovarian mass, adding to the horror stories circulating in the community. Together with others, Karen helped establish Just Moms STL, a group advocating for the clean-up and ensuring that locals receive protection from potential future radiation exposure.

Similar stories echo throughout the neighborhood, creating a web of health crises rooted in local histories. Teresa Rumfelt, who lived close to Karen, consistently bore witness to neighbors suffering from rare illnesses, making her worry escalate when her sister was diagnosed with ALS, tying back to the environmental concerns many residents believe are linked to radiation.

Although some professionals might downplay the connection between illnesses and the exposure from Coldwater Creek, the sense of dread persists. Dr. Gautum Agarwal acknowledges attending patients from the area presenting with cancer but points out that statistical evidence remains inconclusive, ultimately suggesting enhanced screening for those living nearby. Roger Lewis, an expert in environmental health, emphasizes that while the perceived risk exists, studies show minimal correlation. Nonetheless, the government’s response to community fears lacks transparency, only heightening worries.

As Kim Visintine aptly conveys, many residents live under the grim inevitability that illnesses will touch their lives sooner or later. This ongoing struggle for the people of Coldwater Creek continues to draw attention as they seek answers and advocacy amidst a troubling history of nuclear waste and health risks.