A sea of people flowed along the roads leading up to Novi Sad railway station.

They came in their tens of thousands to remember the 16 people who died there this time last year, on another unseasonably warm and sunny autumn day.

The victims were standing or sitting underneath a concrete canopy at the recently-renovated facility when it collapsed. The two youngest were just six years old, the oldest, 77.

Regular protests have rocked Serbia in the 12 months that have followed. But on Saturday morning, the huge crowd participated in an event that emphasized quiet commemoration.

At 11:52 (10:52 GMT), the time of the disaster, they observed a silence for 16 minutes - one for each of the victims. Family members cried. One woman needed to be physically supported by men wearing the red berets of armed forces veterans.

After the silence, relatives laid flowers at the front of the station.

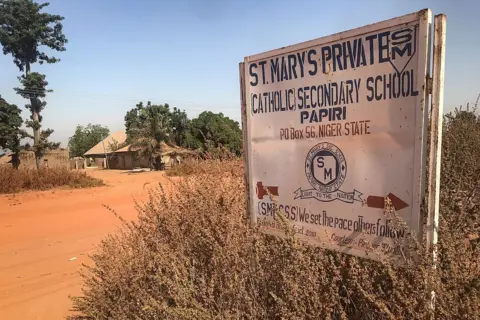

The rubble of the collapsed canopy has been cleared away, but the building appears to have remained untouched since the disaster.

Twisted metal protruding from the walls and broken glass still offer evidence of the catastrophe.

Novi Sad station was supposed to be a symbol of Serbia's progress, under President Aleksandar Vučić's Progressive Party. The country's second city would be a key stop on the high-speed railway line whipping passengers from Belgrade to Budapest in less than three hours.

Vučić and Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban jointly opened the renovated facility in 2022. Its angular, Yugoslav-era form had been upgraded as part of the high-speed project.

But after the disaster, the station now stands as a prime example of everything that is wrong in Serbia.

For the government's flagship infrastructure project to prove deadly to its citizens was more than many could bear. They took to the streets, carrying placards reading corruption kills.

University students quickly took leadership, distancing their movements from political opposition parties that have historically failed to garner trust.

The students have shunned the opposition parties and are now calling for fresh elections, promising to submit a list of independent candidates to reform Serbian institutions.

In September, 13 people, including former construction, infrastructure, and Transport Minister Goran Vesić, were charged in connection with the collapse. Despite the evidence against them, the government has denied accusations of corruption.

This day may have been about respect and remembrance, but the anger remains palpable among the people.