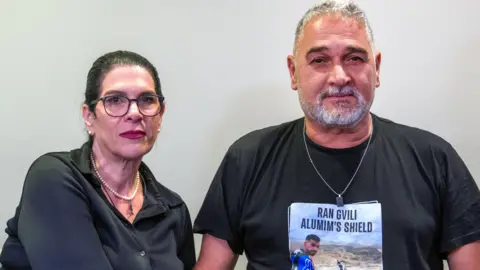

LEXINGTON, Neb. (AP) — On a frigid day after Mass at St. Ann’s Catholic Church in rural Nebraska, worshippers shuffled into the basement and sat on folding chairs, their faces barely masking the fear gripping their town.

A pall hung over the room just as it hung over the holiday season in Lexington, Nebraska.

“Suddenly they tell us that there’s no more work. Your world closes in on you,” said Alejandra Gutierrez.

She and the others work at Tyson Foods’ beef plant and are among the 3,200 people who will lose their jobs when Lexington’s biggest employer closes the plant next month after more than two decades of operation.

Hundreds of families may be forced to pack up and leave the town of 11,000, heading east to Omaha or Iowa, or south to the meatpacking towns of Kansas or beyond, causing spinoff layoffs in Lexington’s restaurants, barbershops, grocers, convenience stores and taco trucks.

“Losing 3,000 jobs in a city of 10,000 to 12,000 people is as big a closing event as we’ve seen virtually for decades,” said Michael Hicks, director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at Indiana’s Ball State University. It will be “close to the poster child for hard times.”

All told, the job losses are expected to reach 7,000, largely in Lexington and the surrounding counties, according to estimates from the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, shared with The Associated Press. Tyson employees alone will lose an estimated $241 million in pay and benefits annually.

Tyson says it’s closing the plant to “right-size” its beef business after a historically low cattle herd in the U.S. and the company’s expected loss of $600 million on beef production next fiscal year.

The plant’s closure threatens to unravel a Great Plains town where the American Dream was still attainable, where immigrants who didn’t speak English and never graduated high school bought homes, raised children in a safe community and sent them to college.

Now, those symbols of economic progress — mortgages and car payments, property taxes and tuition costs — are bills that thousands of Tyson workers won’t have an income to pay.

At St. Ann’s church, Gutierrez sat between her daughters and recalled being told of the plant closure just before Thanksgiving while she visited a college campus with her high school senior, Kimberly.

“At that moment, my daughter said she no longer wanted to study,” Gutierrez said. “Because where would we get the money to pay for college?”

A tear slipped down Kimberly’s cheek as she looked at her mother and then down at her hands.

“Tyson was our motherland,” said plant worker Arab Adan. The Kenyan immigrant sat in his car with his two energetic sons, who asked him a question he has no answer to: “Which state are we gonna go, daddy?”

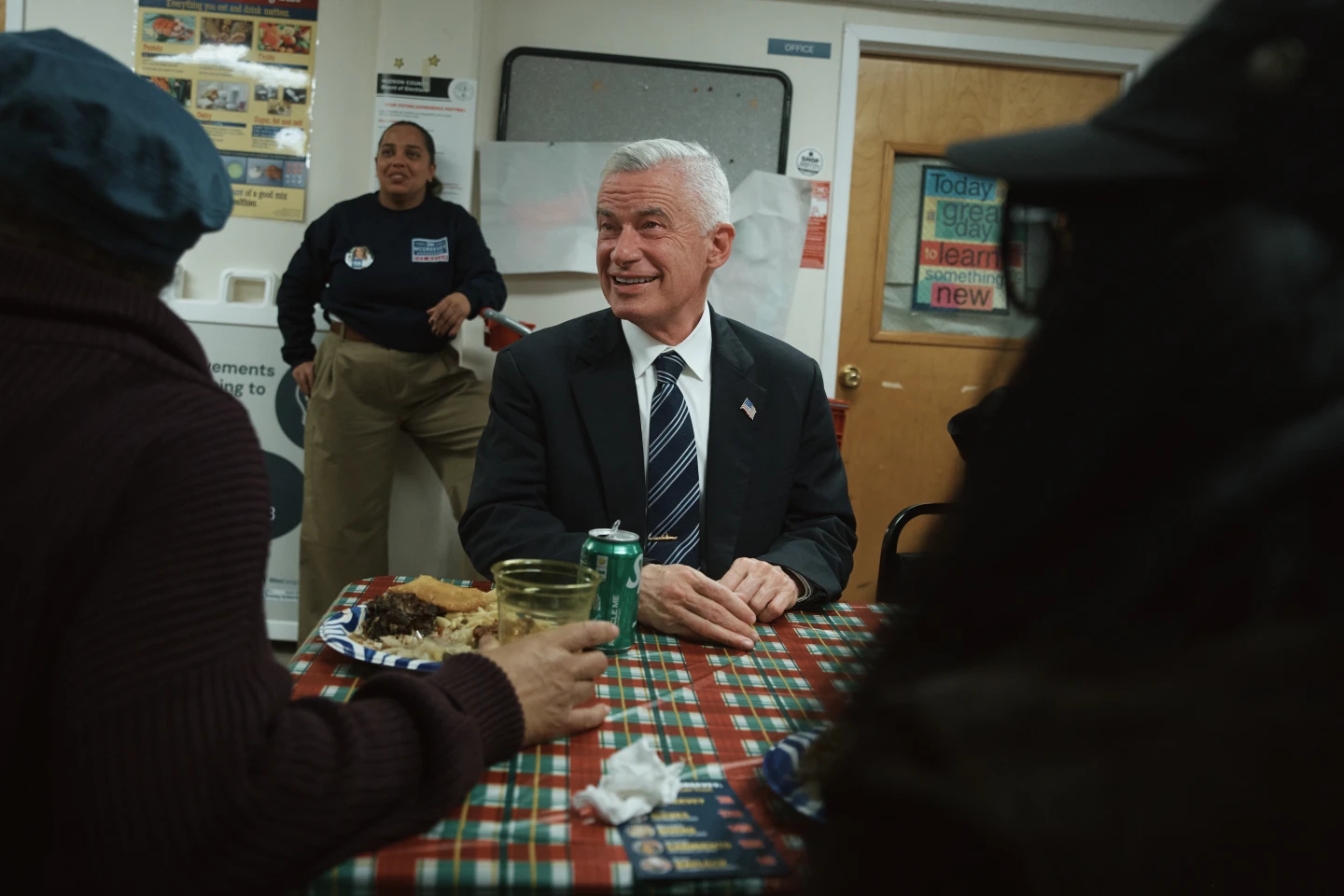

Near the plant, at the Dawson County Fairgrounds, Tyson workers recently filled a long hall as state agencies — responding with the urgency of a natural disaster — offered information on retraining, writing a resume, filing for unemployment and avoiding scammers when selling homes.

Based on the discussions, community members agree that they hope Tyson puts the plant up for sale to attract a new company that could bring back jobs, although many worry about how quickly this could all happen. Hopes hinge on Tyson taking some responsibility to help the community that has supported them for years.