Luis Martinez was on his way to work on a frigid Minneapolis morning when federal agents suddenly boxed him in, forcing the SUV he was driving to a dead stop in the middle of the street.

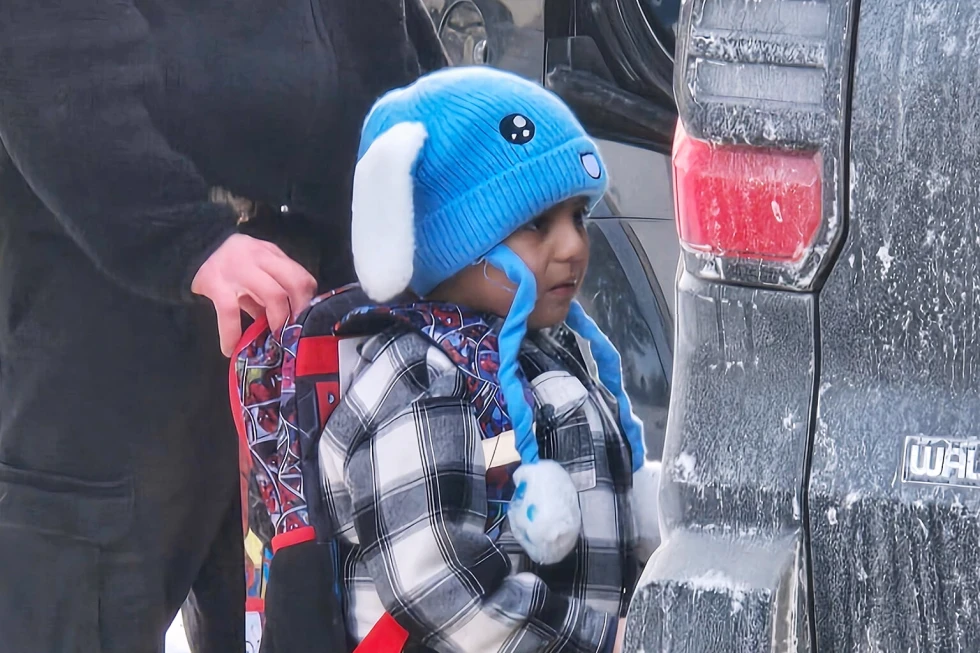

Masked agents knocked on the window, demanding Martinez produce his ID. One agent held his cellphone inches from Martinez’s face, scanning his features to capture the shape of his eyes, the curves of his lips, and the details of his cheeks. All the while, the agent continuously asked, Are you a U.S. citizen?

This encounter in a Minneapolis suburb highlights the aggressive tactics employed in the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown in Minnesota, touted as the largest of its kind. It has drawn national scrutiny, especially after federal agents shot and killed two U.S. citizens earlier this month.

Government officials assert that enforcement efforts are targeted and focused on serious offenders, but evidence suggests otherwise. Photographs, videos, and internal documents reveal a reliance on biometric surveillance and interconnected databases, showing how a vast digital monitoring system has become integral to the administration's approach to immigration enforcement.

Civil liberties experts warn that the expanding use of these systems risks sweeping up both citizens and noncitizens without substantial transparency or oversight.

Over the past year, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and related agencies have significantly enhanced their capabilities to collect, share, and analyze personal data. This involves collaborations with local, state, and federal agencies, as well as contracts with tech companies and data brokers. The resulting databases encompass immigration and travel records, facial images, and information drawn from vehicle databases.

In Martinez’s case, the facial scan yielded no matches, and it wasn't until he presented his U.S. passport—carried out of concern for such encounters—that federal agents finally allowed him to leave.

“I had been telling people that here in Minnesota it’s like a paradise for everybody, all the cultures are free here,” he lamented. “But now people are running out of the state because of everything that is happening. It’s terrifying. It’s not safe anymore.”

With the support of surveillance data and technologies, federal authorities can now monitor American cities on a scale once thought unimaginable. Agents can identify individuals through facial recognition technology, trace their movements using license-plate readers, and, in some situations, utilize commercially available phone location data to reconstruct daily routines and social connections.

When approached for comment regarding its use of surveillance tools, DHS declined to disclose law enforcement-sensitive methods, justifying the technology as essential for apprehending gang members, drug dealers, and other criminals while still respecting civil liberties.

However, critics argue that the government’s access to such extensive datasets poses a direct threat to privacy rights and civil liberties. Dan Herman, a former senior adviser at Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and now at the Center for American Progress, cautions against the potential abuse of this data.

“Everyone should be very concerned about the potential that this data could be weaponized for improper purposes,” he said.

The increasingly invasive measures extend to facial recognition, as DHS recently revealed it has been using a mobile application called Mobile Fortify. This app compares facial scans taken by agents to verify identities using predefined source photos.

Such surveillance technologies complicate the balance between security needs and civil rights, as agents typically scan individuals without seeking consent, often disregarding objections. The situation has fueled anxiety among residents who previously viewed the state as a welcoming and safe environment. With ongoing developments in surveillance technologies, the implications for immigration enforcement, public privacy, and social justice continue to unfold.