In 2025, soaring gold prices are capturing global attention, providing a safe haven amid economic uncertainty. However, the story behind this precious commodity is dark, especially in West Africa's Sahel region, where it is increasingly tied to conflict and military operations. Central banks, hedge funds, and retail investors are all vying for gold, yet many remain unaware of its origins or the turmoil it may be perpetuating.

For the military governments in the troubled Sahel countries of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, gold represents crucial funding as they grapple with jihadist threats, climate change, and economic challenges. According to Beverly Ochieng, a researcher at Control Risks, the juntas hope to reap financial dividends from the spike in gold prices. As these nations collectively produce approximately 230 tonnes of gold annually, estimated at around $15 billion, they stand tall as Africa’s leading gold producers. However, much of this output stems from unregulated artisanal mining, which may be underreported.

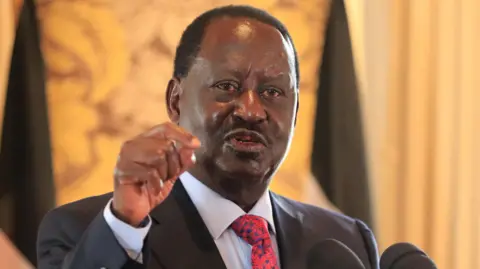

The governments declare that the wealth generated from gold mining will enhance national autonomy, yet recent partnerships with Russian firms suggest that Western interests are being sidelined. Notable initiatives include the establishment of a gold refinery in Mali led by the Russian Yadran Group, promising job creation but also raising concerns about increasing Russian influence in the region. Meanwhile, Burkina Faso is developing its own gold refinery and creating a state-owned mining entity, compelling foreign firms to cede a share of their operations. This has fueled a misleading narrative around the nation’s young military ruler, Capt Ibrahim Traoré, celebrated through AI-generated media as a hero of gold revenue.

Despite the glamor associated with gold, reality tells a grimmer story. The revenue stream from gold extraction is heavily funneled into military expenditures, particularly in the fight against jihadist groups, which have increased attacks in the region. Human Rights Watch has documented grave accusations against both the Malian military and the Wagner Group, including unlawful killings and torture of civilians. Reports suggest that these armed groups not only engage in illegal gold mining but could also be benefiting from the soaring demand for this resource.

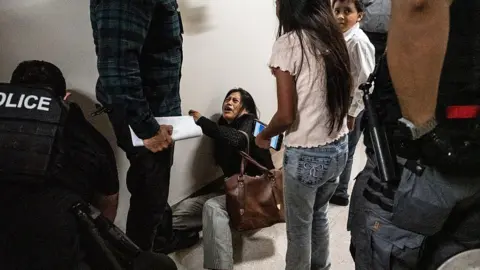

A significant portion of gold mining in the Sahel takes place in the informal sector, away from government oversight. The race for control between state forces and armed groups over these small-scale operations poses further risks to local communities, who may find themselves in harm’s way as both sides vie for revenue. Artisanal miners often face risks without seeing any fair financial return; a miner from Mali described how their earnings remained stagnant despite global price increases, signifying a disparity in wealth distribution.

Dr. Alex Vines, an expert on conflict commodities, likened gold to Africa's new "blood diamond," raising alarms over the issue's persistent obscurity compared to past crises. Unlike diamonds, which went through enhanced regulatory scrutiny with the Kimberley Process, ethical standards that might govern gold mining are largely ineffective. Weak mandates in the UAE and the LBMA's voluntary guidelines struggle against the illicit nature of much gold sourcing, leaving markets open to conflict-associated resources.

For communities affected by conflict in the Sahel, the reality of "blood gold" may be inescapable. Even as the international gold market flourishes, efforts to trace the origins of gold remain lacking, complicating the potential for ethical reform. As long as Sahel governments benefit from this revenue stream amidst a backdrop of violence and instability, the grim reality is that profits from this shimmering allure may continue to exacerbate the plight of those they are meant to help.