The American Southwest is experiencing a megadrought that has severely impacted water access, agriculture, and increased wildfire risks for nearly 25 years. This relentless dry spell is the longest such period recorded in over a millennium, and unfortunately, new research indicates that conditions may not improve for decades.

A study published in Nature Geoscience reveals that this drought is not merely a short-term setback but is driven by an entrenched pattern of Pacific Ocean temperatures exacerbated by global warming. Victoria Todd, a doctoral student in paleoclimatology at the University of Texas at Austin, emphasizes that the drought could extend well into 2050, potentially lasting until 2100 or longer if global temperatures continue to rise.

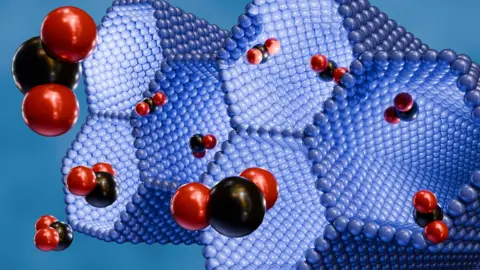

The study highlights the severe consequences of prolonged dryness, particularly in a region dependent on sufficient water supply for agriculture and burgeoning industries, including tech manufacturing, which require significant water resources. Todd and her team investigated past droughts by examining sediment cores from Stewart Bog in New Mexico and Hunters Lake in Colorado. This sediment analysis revealed insights into historical moisture levels over millennia.

Their findings correlate with a period approximately 6,000 years ago characterized by warm temperatures that led to substantial annual drying spells. The research indicates that during this time, a consistent patch of warm water in the Pacific redirected storm patterns away from the Southwest, resulting in continuous dry conditions. Unlike that ancient period, where the patterns fluctuated, contemporary warming appears to lead to a static warm patch that could perpetuate drought conditions.

Dr. A. Park Williams, a climate scientist from UCLA, commended the thoroughness of the study but pointed out that current climate models may underestimate the extent to which these warm water patterns could exacerbate drought in the Southwest. This situation underscores human influences on climate, as global warming accelerates these processes, drying out soil and shifting precipitation patterns.

Significant shifts occurring in climate patterns now challenge established weather norms. For instance, despite expectations, the recent El Niño phase did not result in the wetter winters typically associated with such an event. Dr. Pedro DiNezio from the University of Colorado Boulder argues that these disconnections from expected climate behaviors suggest profound effects of anthropogenic climate change on environmental rhythms.

As scientists continue to uncover the implications of historical climate data, understanding the potential longevity of this megadrought becomes increasingly critical for the millions relying on the water resources of the American Southwest.

A study published in Nature Geoscience reveals that this drought is not merely a short-term setback but is driven by an entrenched pattern of Pacific Ocean temperatures exacerbated by global warming. Victoria Todd, a doctoral student in paleoclimatology at the University of Texas at Austin, emphasizes that the drought could extend well into 2050, potentially lasting until 2100 or longer if global temperatures continue to rise.

The study highlights the severe consequences of prolonged dryness, particularly in a region dependent on sufficient water supply for agriculture and burgeoning industries, including tech manufacturing, which require significant water resources. Todd and her team investigated past droughts by examining sediment cores from Stewart Bog in New Mexico and Hunters Lake in Colorado. This sediment analysis revealed insights into historical moisture levels over millennia.

Their findings correlate with a period approximately 6,000 years ago characterized by warm temperatures that led to substantial annual drying spells. The research indicates that during this time, a consistent patch of warm water in the Pacific redirected storm patterns away from the Southwest, resulting in continuous dry conditions. Unlike that ancient period, where the patterns fluctuated, contemporary warming appears to lead to a static warm patch that could perpetuate drought conditions.

Dr. A. Park Williams, a climate scientist from UCLA, commended the thoroughness of the study but pointed out that current climate models may underestimate the extent to which these warm water patterns could exacerbate drought in the Southwest. This situation underscores human influences on climate, as global warming accelerates these processes, drying out soil and shifting precipitation patterns.

Significant shifts occurring in climate patterns now challenge established weather norms. For instance, despite expectations, the recent El Niño phase did not result in the wetter winters typically associated with such an event. Dr. Pedro DiNezio from the University of Colorado Boulder argues that these disconnections from expected climate behaviors suggest profound effects of anthropogenic climate change on environmental rhythms.

As scientists continue to uncover the implications of historical climate data, understanding the potential longevity of this megadrought becomes increasingly critical for the millions relying on the water resources of the American Southwest.