NASA is accelerating its efforts to implement a nuclear reactor on the Moon by the end of the decade, according to reports from U.S. media outlets. This ambitious project is part of a broader strategy to establish a sustainable human presence on the lunar surface, which has gained renewed attention amidst global competition from nations such as China and Russia.

The acting head of NASA cautioned that these countries might soon claim exclusive territories on the Moon, underscoring the urgency of U.S. plans. Despite these intentions, many experts question whether NASA can achieve its timeline, especially considering recent budgetary constraints and skeptical opinions from within the scientific community.

U.S. Secretary of Transportation Sean Duffy, who has stepped in as the interim head of NASA, emphasized the importance of moving forward swiftly with the Fission Surface Power Project. He has solicited commercial proposals for a reactor capable of generating a minimum of 100 kilowatts, which is significantly lower than the capacity of typical onshore wind turbines.

The idea of deploying nuclear reactors on the Moon is not groundbreaking; previous contracts worth $5 million were awarded by NASA in 2022 to design such technology. Simultaneously, China and Russia have announced plans to construct a nuclear power facility on the Moon by 2035.

Experts argue that nuclear energy may be the most effective method for generating continuous power on the lunar surface, where daylight is divided into two weeks of sunshine followed by two weeks of darkness, complicating reliance on solar energy. Dr. Sungwoo Lim, a senior lecturer in space applications, echoed this sentiment, asserting that the need for megawatt-scale power generation for lunar habitats makes nuclear power a necessity.

Professor Lionel Wilson from Lancaster University stated that if appropriately funded, placing reactors on the Moon by 2030 is technically feasible, provided that NASA's Artemis program can facilitate the necessary launches and infrastructure developments.

Nonetheless, significant safety concerns remain, primarily regarding the transportation of radioactive materials through Earth's atmosphere, which requires special permits. Recent budget cuts, amounting to a 24% reduction set for 2026, have raised alarms among scientists. Critics, including Dr. Simeon Barber from the Open University, have pointed out that the recent directives seem politically motivated, resembling the competitive environment of the original space race, which could detract from collaborative scientific goals.

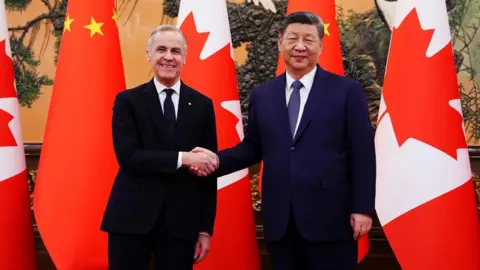

Duffy's comments highlight the potential for China and Russia's future claims on lunar territory, referencing the Artemis Accords signed by seven nations to promote cooperative governance of the Moon. The assertion that establishing a nuclear reactor could allow the U.S. to claim exclusive jurisdiction on lunar regions raises ethical questions, with Dr. Barber noting that this could hinder scientific exploration and international cooperation.

As NASA prepares for its Artemis 3 mission, which aims to land humans on the Moon by 2027, challenges remain. There are growing concerns that without a cohesive strategy to address transportation and infrastructure, the ambitious plans for a lunar nuclear reactor may not materialize as intended. The complex balance between space exploration and national interests continues to evolve in this new era of cosmic ambition.