As worries over a potential Russian invasion intensify, many ordinary Poles have begun engaging in military training initiatives to prepare themselves for possible armed conflict. In Wroclaw, civilians line up at military training grounds to learn how to operate firearms and gain survival skills amidst rising tensions in Eastern Europe. The program, aptly named "Train with the Army," is promoting self-defense courses that teach not just shooting, but also hand-to-hand combat, medical aid techniques, and proper procedures for donning gas masks.

"We are living in dangerous times, and we need to be ready," asserts Captain Adam Sielicki, the program's coordinator. With a sharp emphasis on national security, Captain Sielicki highlights plans to expand training so that every adult male in Poland can receive military preparation. Poland has pledged to allocate nearly 5% of its GDP to defense this year—the highest commitment among NATO member nations—reflecting its determination to enhance military capabilities.

In a recent statement, Prime Minister Donald Tusk laid out goals for Poland to establish "the strongest army in the region." The government has been actively procuring defense systems, including aircraft, naval vessels, artillery, and missiles from international partners, primarily the United States, Sweden, and South Korea.

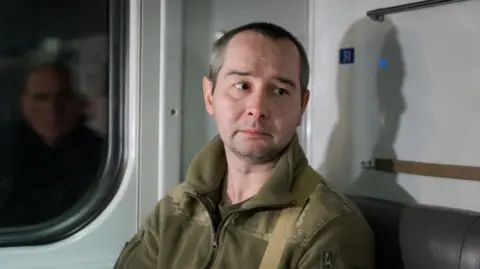

Among the aspiring combatants, Dariusz eagerly shares his commitment to defend the nation if aggression were to occur. "History has taught us to prepare for self-defense,” he expresses. “Relying on others may lead to dire consequences." Another participant, Agata, notes that the geopolitical climate, particularly the unpredictability surrounding Donald Trump's presidency, has contributed to a growing sense of insecurity regarding transatlantic alliances. "If we do not prepare ourselves and a Russian attack occurs, we could find ourselves subjugated," she cautions.

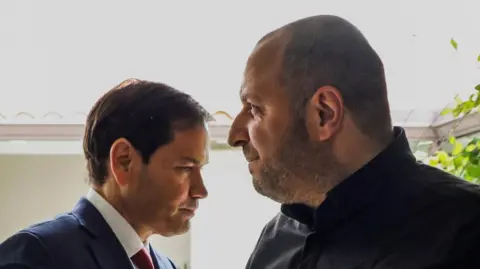

The presence of U.S. troops—approximately 10,000 stationed in Poland—has previously lent a sense of security. However, recent pullbacks and statements indicating a changing posture from Washington have left Polish officials jittery. Tomasz Szatkowski, Poland’s representative to NATO, reflects this unease, suggesting the need to explore broader defense strategies in light of changing dynamics in international relations.

A century-long shadow looms as many Poles still feel the consequences of past occupations. Wanda Traczyk-Stawska, now 98, remembers the last Russian invasion in 1939 vividly and advocates for a strong military to deter future hostilities. "Better to be well-armed than wait for trouble to find us," she implores.

In unison with these concerns, the demand for bomb shelters in Poland has skyrocketed, with manufacturers like Janusz Janczy reporting a steady increase in inquiries. "People are building these shelters simply because they don't know what to expect tomorrow," he admits.

Despite these increased preparations, a survey revealed ambivalence among the public: only 10.7% expressed willingness to join the army as volunteers should war arise, indicating that although fears of conflict are plentiful, actual resolve to defend the nation remains tepid. Some Polish students, like medical student Marcel, expressed a sense of detachment from the prospect, revealing a tendency to consider flight over fighting.

As the geopolitical landscape shifts and Poland gears up for potential conflict, the juxtaposition of readiness and reluctance remains a complex narrative shaping the national psyche.